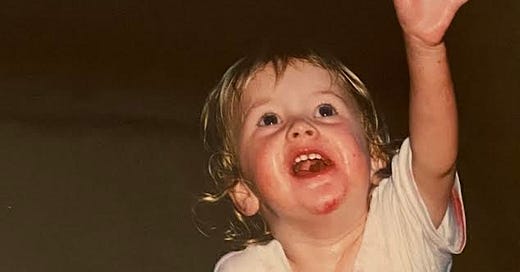

It’s the morning after a snowstorm, and there is panic in the Richtman household. Pops swings Caitlyn through the air. Once, twice. She is five years old, maybe six, and screaming in her footie pajamas. I scream too. Pops counts.

“One!”

The back door of our Ohio home is wide open, and there’s at least three or four feet of snow just outside the door.

“Two!”

This is it. This is the end. So long, Caitlyn. Our time together was brief, but I’ll always remember you fondly.

“Three!”

Caitlyn shrieks louder. At the last second, Pops changes his mind and sets her down on the floor. Phew. The snow did not win today. I still have four sisters safe and sound inside our warm kitchen.

My relief is short-lived.

Pops picks me up next. I scream. I thrash. I look at Caitlyn. Time moves more slowly when you’re headed for a snowy death. As Pops lifts me to my doom, Caitlyn shouts with her hand outstretched to me, “It’s okay! He didn’t throw me! He won’t throw you!”

“One!”

That makes sense. Pops is a predictable man. He eats the same thing for breakfast every morning. He comes home from work at the same time every evening. If I ask him to make my Saturday pancake in the shape of a princess, he makes it in the shape of a princess.

“Two!”

If he didn’t throw Caitlyn, he certainly won’t throw me. I’m smaller than her, younger than her. I laugh because this guy can’t trick us. Fool us once, shame on you. Fool us twice, shame on—

“Three!”

Plop.

I had been fooled. By my own father. I sprung up from the snow laughing.

When I tell this story to people, I still laugh. This is one of my earliest memories, maybe the earliest memory, I have of my childhood. I love telling it because it is so Pops. A couple of years later, we’d moved from that house in Ohio to Georgia, where we have a pool in the backyard. Like a lot of kids, I was afraid to jump into the deep end. I was a strong swimmer because I’d been taking lessons for years, but no one is better at convincing you you’re incompetent than your own fear. Especially at eight years old. Eventually, Pops got tired of watching me whine at the edge of the water and pushed me in. You might disagree with his methods, but they are effective.

I’ve never been afraid of pools or snow since.

We’ve got some catching up to do. At the start of the year, I published my first substack post where I boldly announced I wanted to work as an au pair in Paris, France. Not long after that, I stopped pursuing that goal while I brainstormed other ways to turn my dream of living abroad into a reality.

My next few newsletters included sharing about a spontaneous trip to Colombia, a reflection on the first time I visited the country, a review of a travel memoir, and local adventures. Most of these posts have gone out to my paid subscribers only, and it’s been a really fun stretch of experimentation with my writing. My earliest subscribers, particularly the folks backing me financially, are near and dear to my heart. I’m not sure I’d be where I am today without them.

Where am I exactly? I’m at the Savannah Airport, where so many of my best travel stories start. I won’t be in Georgia, the place I’ve called home for 19 years, for much longer. This trip—can you really call it a trip when you’ll have an apartment, bank account, and job in another country?—will be the longest I’ve ever been away from Georgia.

Why am I at the Savannah Airport? I’m about to get on a plane, which will take me to another plane, which will take me to Seoul, South Korea. I’m moving there to teach English as a foreign language. Earlier this year, I got my TEFL certification. In June, I signed a teaching contract at a school in Korea. In July, I went to Atlanta for a visa appointment. Last week, I bought a one way plane ticket.

Why South Korea? The short answer: Why the hell not!

The longer answer: South Korea has some of the best salaries/benefits for TEFL teachers around the world. For that reason, it’s been on my radar for a while, but I learned a wonderful piece of magic earlier this year: Some of the best places we end up seeing are the unexpected ones.

When you’re a toddler, your world is as big as the palm of your hand. Snow is scary until the moment you land. Then it’s a private kingdom. When you’re eight years old, your world is as far as you can stretch your fingers. The deep end is scary because you can’t touch all of it.

When you’re twenty-two, the world keeps going as long as you’ve got enough gas in the car to get you there. Jumping from your raft into a clear blue, ice-cold Montana river is nerve-wracking, especially with all those people watching you. But you said you’d do it and you’ve long since learned the reward is worth the risk. Or, you’re committed to learning and relearning it. You’re the only one to jump in. Your life-jacket lifts you up with the current. You’re laughing like a little kid, delirious with it.

I suppose the story actually starts last fall. My sister and I took a month-long RV trip around the southeastern United States. We kayaked at Congaree National Park while the mid-October sun still blazed, sipped red wine in Asheville, in Cherokee, in Helen as the leaves changed, and hiked to the top of Mount Yonah in north Georgia.

I didn’t have a plan. Or, I thought I did: How does a person become an au pair? You already know how that plan worked out.

I didn’t have a plan. Or, I did, but it didn’t look like the plans my friends or peers had. Today, I will wake up before the sun to watch the elk graze in the valley. Today, I will go to every bookstore in Asheville. Today, I will write my novel. Today, I will climb a mountain.

On our way up Mount Yonah, we ran into an old man with snow-white hair from the Netherlands. He carried a backpack longer than his torso that looked like it weighed more than his entire body weight. As we hiked together—the man, setting a brisk pace and me, breathing heavily—he told us his backpack held paragliding equipment. He and a buddy, a young guy about my age, were going to paraglide off the top of the mountain.

When we all reached the peak, the younger guy went first. About twenty of us gathered around as he stepped into his gear, did a safety check, and spread out his parachute. Folks were asking him questions, which he answered with what I guessed was probably only about 30% of his attention. The rest of his attention was on the task at hand.

A bird was already out there, soaring between our mountain and the next. The world was a warm color palette in mid-November. All reds and oranges. Mount Yonah’s elevation is over 3,000 feet.

Someone asked him when he’d go.

With his back turned to us, he said, “It’s all about the wind. When the right wind comes, I can’t hesitate. I have to jump.”

Last month, I shared a post with my paid subscribers that was about fear. When you decide to move to a foreign country, that’s the topic at the forefront of your mind. In part, this is because moving abroad is scary. I see no use in lying to you about that. I’m pretty sure it would be more alarming if I told you that I wasn’t scared at all. What kind of fool isn’t scared to leave everything and everyone they know behind? What kind of fool lives their whole life in a bubble, too?

But the other part of this is that fear is so central because everyone around you is afraid too. Or, not everyone, but the ones who are afraid seem to think you haven’t thought this all the way through. At a house party a few weeks ago, a friend looked me right in the eye and said, “It’s stressing me out that you’re doing this.”

I laughed and said, “It’s stressing you out?”

If I stopped every time I felt fear, I would never get anything done. I’d still be at the edge of that pool.

The total population of Georgia is 10 million people. The county where I grew up has about 65,000 people.

South Korea’s population is just shy of 52 million. Roughly half of that population lives in the Seoul area, where I’ll be living.

Georgia is a little less than 60,000 square miles.

South Korea is 38,000 square miles.

These are just numbers. I want to know how it feels.

If you take the long way home around here, you’ll pass my elementary school where I wrote my first short story. You’ll pass the patch of woods they ran through when the cops broke up the party. Eighteen and drunk and stupid. You might take I-95 into South Carolina, just to turn around at the first exit and come back to Georgia. You’ll pass the man who stands out by his mailbox and waves at the cars driving by. Make sure you wave back. You’ll follow the same roads Jamie and I drove the day “drivers license” by Olivia Rodrigo dropped. Stop at this intersection for a second. This is where Jacqueline showed me the first ultrasound of the baby. No bigger than a sweet pea. That’s the house I’d buy if I was a millionaire. Those are the houses I’d buy if I was a billionaire. You’ll pass where the time capsule is buried. The yellow house and the one with the rainbow flag and the one Melanie said she likes. Maybe you’ll drive out to the tupelo trees. They promise to remember even when we are quick to forget. You’ll probably want to take the road with the sharp corner that passes the cows. If you’re riding shotgun and the night sky holds nothing but stars and you’ve got a sunroof, use it. Pass the elementary school where my mom works. They’ve got copies of all their new student paperwork translated into Korean now because of the Hyundai plant coming to Savannah. If you feel like you’ve started going in circles, you’ve done it right.

When the wind came and he finally jumped off Mount Yonah, it didn’t look scary. It looked almost gentle—if you’ll believe it. Once he jumped, there was nothing left to do but fly. If you’re still worried, stressed, or scared for me, do me a favor and remember the first thing Caitlyn shouted as Pops lifted me into the air: It’s okay.

Trust Caitlyn to get the details wrong but everything else right.

Boarding starts soon. I’ve got to go. Whatever comes next, I know I want to tell you about it. I hope you’ll come along with me for this next adventure on The Long Way Home.